Plant Hardiness Zone- Has Yours Changed?

Know Your Plant Hardiness Zone Before You Plant!

Click on the US map for a large version of the lower 48 or find a detail map of your state in the list below. If your hardiness zone has changed in this edition of the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map (PHZM), it does not mean you should start pulling plants out of your garden or change what you are growing. What is thriving in your yard will most likely continue to thrive.

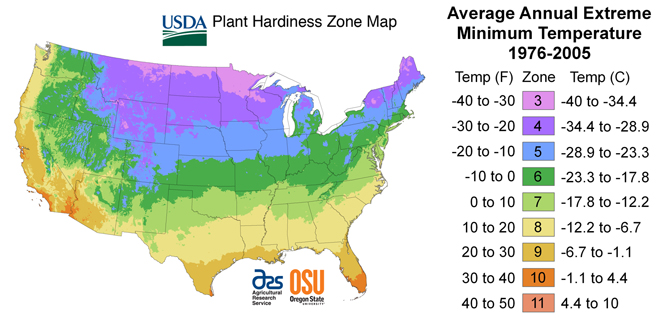

This is the 2012 USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map. It is the standard for gardeners and growers to determine which plants have the best chance to thrive in a particular location. The map is based on the average annual minimum winter temperature and is divided into 10-degree Fahrenheit zones. The state maps are divided into 5-degree zones.

View Your Detailed State Hardiness Zone Map In The List Below

Arizona

Arkansas

California-North

California-South

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

District of Columbia

Florida

Georgia

Idaho

Illinois

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Hardiness zones are determined by the average annual lowest temperature as measured over a 30-year period in the past, not the record low temperature that has ever occurred in the past or might occur. Gardeners should consider that when selecting plants, especially if they choose to “push” their hardiness zone with plantings not rated for their zone. In addition, although the edition of the USDA PHZM presented here is the most detailed scale to date, and there may be microclimates too small to show up on the map.

Microclimates, which are fine-scale variations in climate, can be heat islands—such as those caused by blacktop and concrete, cities and towns, and cool spots as a result of the effect of small hills and valleys. Even individual gardens may have a very localized microclimate. Your entire yard could be slightly warmer or cooler than the surrounding area due to being sheltered or exposed. There may be pockets within your garden that are warmer or cooler than the general zone for your area or for the rest of your yard, such as a sheltered area in front of a south-facing wall or low spots where cold air pools first. Hardiness zone maps can’t take the place of the detailed knowledge that experience with your own gardener will bring you.

Many plant species acquire cold hardiness gradually in the fall as the days get shorter and temperatures cool. This hardiness normally disappears slowly in late winter as warmer temperatures and longer days arrive. Keep in mind that a spell of extremely cold weather in the early fall can harm plants even though the temperatures may not reach the average lowest temperature for your zone. Similarly, exceptionally warm weather in midwinter followed by a sharp change to seasonably cold weather may cause injury to plants as well. Such factors are not taken into account in the USDA PHZMs (Plant Hardiness Zone Maps) presented on this site.

All PHZMs are just guides. They are based on the average lowest temperatures, not the record lowest ever. Growing plants at the extremes of the coldest zone where they are adapted means that they could experience a year with a rare, extreme cold snap that lasts just a one or two days, and plants that have thrived happily for several years could be lost. Gardeners need to keep that in mind and understand that past weather records cannot be a guarantee for future variations in the weather.

Other Factors

Other factors in the environment, in addition to hardiness zones, contribute to the success or failure of plants. Wind, soil type, soil moisture, humidity, pollution, snow, and winter sunshine can all greatly affect the survival and ability of plants to thrive. The way plants are placed in the landscape, how they are planted, and their size and health might also influence their survival.

Soil moisture: Plants have different requirements for soil moisture, and this might vary seasonally. Plants that might otherwise be hardy in your zone might be injured if soil moisture is too low in late autumn and they enter dormancy while suffering moisture stress.

Light: To thrive, plants need to be planted where they will receive the proper amount of light. For example, plants that require partial shade that are at the limits of hardiness in your area might be injured by too much sun during the winter because it might cause rapid changes in the plant’s temperature.

Temperature: Plants grow best within a range of optimum temperatures, both cold and hot. That range may be wide for some varieties and species of plants but very narrow for others.

Duration of exposure to cold: Many plants that can survive a short period of exposure to cold may not tolerate longer periods of cold weather.

Humidity: High relative humidity limits cold damage by reducing moisture loss from leaves, branches, and buds. Cold injury can be more severe if the humidity is low, especially for evergreens. One reason why adequate watering in the fall may help some plants through the winter.